“There could be only one explanation for such results: In response to the

trauma itself, and in coping with the dread that persisted long afterward, these

patients had learned to shut down the brain areas that transmit the visceral

feelings and emotions that accompany and define terror. Yet in everyday life,

those same brain areas are responsible for registering the entire range of

emotions and sensations that form the foundation of our self-awareness, our

sense of who we are. What we witnessed here was a tragic adaptation: In an

effort to shut off terrifying sensations, they also deadened their capacity to feel

fully alive.

The disappearance of medial prefrontal activation could explain why so

many traumatized people lose their sense of purpose and direction. I used to be

surprised by how often my patients asked me for advice about the most ordinary

things, and then by how rarely they followed it. Now I understood that their

relationship with their own inner reality was impaired. How could they make

decisions, or put any plan into action, if they couldn’t define what they wanted

or, to be more precise, what the sensations in their bodies, the basis of all

emotions, were trying to tell them?

The lack of self-awareness in victims of chronic childhood trauma is

sometimes so profound that they cannot recognize themselves in a mirror. Brain

scans show that this is not the result of mere inattention: The structures in charge

of self-recognition may be knocked out along with the structures related to self

experience.

When Ruth Lanius showed me her study, a phrase from my classical high

school education came back to me. The mathematician Archimedes, teaching

about the lever, is supposed to have said: “Give me a place to stand and I will

move the world.” Or, as the great twentieth-century body therapist Moshe

Feldenkrais put it: “You can’t do what you want till you know what you’re

doing.” The implications are clear: to feel present you have to know where you

are and be aware of what is going on with you. If the self-sensing system breaks

down we need to find ways to reactivate it.” The Body Keeps the Score by Bessel Van Der Kolk

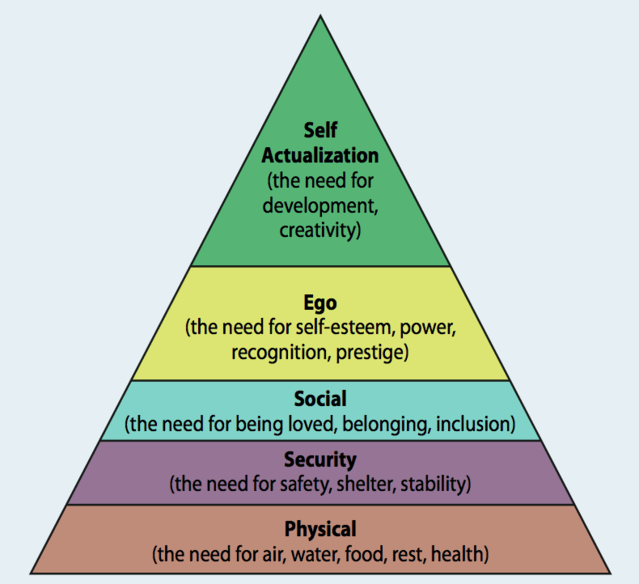

The highlighted portion reminds me a bit of Maslow’s Hierarchy of Needs

“Maslow called the bottom four levels of the pyramid ‘deficiency needs’ because a person does not feel anything if they are met, but becomes anxious if they are not. Thus, physiological needs such as eating, drinking, and sleeping are deficiency needs, as are safety needs, social needs such as friendship and sexual intimacy, and ego needs such as self-esteem and recognition. In contrast, Maslow called the fifth level of the pyramid a ‘growth need’ because it enables a person to ‘self-actualize’ or reach his fullest potential as a human being. Once a person has met his deficiency needs, he can turn his attention to self-actualization; however, only a small minority of people are able to self-actualize because self-actualization requires uncommon qualities such as honesty, independence, awareness, objectivity, creativity, and originality.” Taken from Psychology Today https://www.psychologytoday.com/us/blog/hide-and-seek/201205/our-hierarchy-needs

Rarely have I felt assured of basic needs being met although as a child I believed there would be food on the table. But the rage and anguish weighing down the very air I breathed informed me life was tenuous at best.

One memory that stands out was my husband Pete. There was a brief time before he died that I felt secure, loved, a foundation beneath my feet, and a sense of being “home.” That all disappeared when he died 12 days after we married.

Pete was not a husband in the traditional sense of the word. I meant to never marry or even be open to a relationship. I told him so. He was my best friend. I could not lose that.

But on the day after we got the dire news, he asked me to marry him. He told me he had already left everything he owned to me, and marriage to me would make him happy.

There is a funny story attached to that, but not for today.

Peter Norman Noetling loved me in ways no man had ever. He respected me, was concerned for my well-being, he let me be me and never told me what I “should” feel. When he sensed a rough day he would invite me out for “ice-cream therapy” and he was fine if I talked about it or didn’t. He never made me feel guilty or ashamed for being me. There was no more intimacy than the after college class chats when he switched off the TV at my arrival home and we recounted our day.

My sense of safety left when Pete died. He left me money and a house… but that was not security. Pete was my foundation. Though I fought it desperately, Pete was my “home” and he was gone. I felt torn loose like a balloon in a raging storm.

I am so grateful to have known Pete. I am also grateful that when my anger at him leaving subsided, Pete was still there, nurturing and steady.

It has been said that I never deserved what Pete left me. That hurt me when I heard it. The most important item he gave to me was in the breaking down of my heavy suit of armor I had grown over a lifetime of abuse. He gave me space to feel again. It was not that I wanted to feel, he gave me no choice.

I loved Pete for who he was not what he could do for me or I for him. He was the man who had my back when no other man in my life has thought my back worthy of protecting.

Pete may well be the reason I still strive to recover from the abuse and mud-slinging frenzy of family. Pete gave me a taste of the goodness in life.